One of my favorite things about National Parks is going to Ranger talks/presentations. Many of them are held at the amphitheater in the campground, they usually take place around 7 or 8pm and you often need to bring a blanket to stay warm. The Rangers cover a multitude of topics including specific animals or plants, park ecosystems, specific geographic features (volcanoes), or even activities (rock climbing).

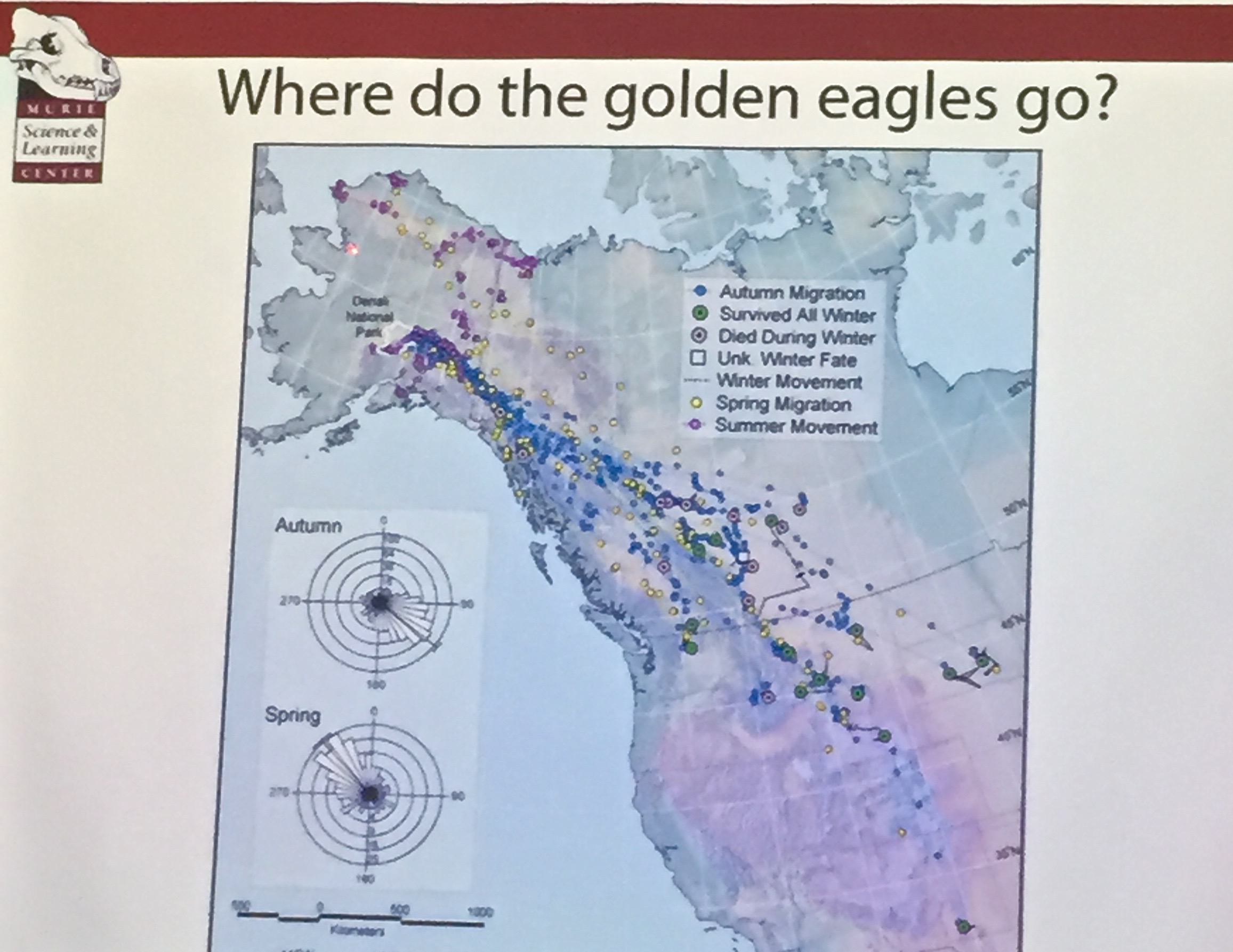

In Denali they had some brown bag lunch presentations, so naturally we attended. The first one that we went to was about Golden Eagles. I am generally not a bird person, but this presenter had the data and laid out an incredible story. It was mind-boggling. She showed us data sets that chronicled the autumn and spring migration of hundreds of eagles. They tracked where they nested in the park and found where they flew in the fall.

If you are wondering how you tag a Golden Eagle so that you can track it, it is really quite simple. You go to a Golden Eagle nest. Which is usually on a rocky cliff. They can be found by looking for orange lichen on rock faces. The lichen is present because it grows where the birds defecate. After you find a nest that has some young fledglings who are incapable of flying. You then rappel down into the nest and tag the bird.

Simple, right?! My first question was, what about the parents?! Do you have to wait until the leave the nest so that you can tag their babies? Nope. You just climb down, the parents will move out of the way and let you mess with their kids. Unbelievable.

One of the more incredible parts about the presentation is that they were able to draw upon data collected in Denali National Park since 1988. One of the things that I don’t think people often realize is that National Parks provide a place for researchers to observe and study animals and plants in their natural habitat. This helps provide us a glimpse into how the world is changing and can actually help us prepare, or change the way that we live. For example, in the 1960’s we noticed that Bald Eagle populations were diminishing. One of the causes is DDT build up in the eagles that caused their eggs to not be viable. If it were not for discovering this we wouldn’t have realized the damage that DDT was causing the environment. You may be thinking, who cares if the entire eagle population died, but that is another conversation for another day. Send me an email and we’ll chat.

We were schedule to leave Denali the following morning, but the Murie Center was having another brown bag lunch presentation. This time the presentation was about the wolves of Denali National Park. Based on the presentation about Golden Eagles I was beyond stoked to learn about the wolves. I couldn’t wait to hear about the data, where the wolves live, what they eat, how many pups they have. I was also excited because Adolph Murie, for who the center was named was prolific for his wolf research.

The wolf presentation was, well it was different. To put it bluntly. It sucked. I don’t mean, oh it wasn’t that good. I mean, why did I waste my time going to this, I could have done anything else.

I don’t want to be unfair, so will try and explain why the wolf presentation left so much more to be desired. Wolves have large ranges. They need lots of space to hunt and provide food for their pack. That means that the wolves that live in Denali often leave the park. Whereas they are protected from hunting and trapping, they are not afforded the same protection outside the park. Often times people will set up baited traps outside the park to attract the wolves and kill them.

If you don’t know why wolves are important, I encourage you to watch this. It’s about Yellowstone National Park, but helps explain the importance of apex predators.

Anyway, one of the things we had read about in park materials was that the wolf population in the park was at an all time low. They think that, in part, it is due to the elimination of buffer zones that protected the park. In 2010, the Alaska Board of Game eliminated several buffer zones that protected the ranges of the wolves. As part of the decision the Board of Game established a moratorium on future public proposals for the next 8-10 years. We read all of this in the Visitor’s Center, and obviously, had all sorts of questions.

Why are the wolf numbers down? Why did the Board of Game make that decision? Who sits on the board? Was the park involved in the process?

The presentation was simply a couple of pictures. It showed pictures of the collars that they put on wolves and the process of putting the collars on the wolves. Basically it was photos of darting wolves from helicopters; there was no data about the population size, what is happening to them. I expected so such and got so little. When we asked about the Board of Game decision and how the park was involved, they didn’t really know.